FIELD WORK

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Relational Listening: sound and (16mm) field recordings

Relational Listening: sound and (16mm) field recordingsWhile historically embalming corpses to some degree existed in the Middle Ages, the mass appeal emerged in the mid 19th century when 11 patents were granted between 1856-1869 coinciding with the American civil war (Sterne, 2003). This Christian practice of preserving also coincided with the invention of recording of sound for ethnographic or funereal purposes, “Both transform the interiority of the thing (body, sound performance) in order that it might continue to perform a social function after the fact.” The ‘record’ was at first ephemeral on fragile materials that deteriorated quite quickly before technological advances guided recordings to become archival. It was used by the Western Bourgeouise and Victorian families to recall the voices of deceased family members or for a brief time for religious ministers to eulogise with sermons at their own funerals (Sterne, 2003). The phonograph was used as a recording device and became an ethnographic tool for researchers and those who aimed to document and preserve cultures, musicians, and the voices of the living (the ethics, methods, or opinions of those at the time are beyond the scope of this essay). The change over time from recording sound for preservation or historical purposes on vinyl to field recording for artistic purposes began to take shape first in the departure from musical or religious pressings through the avant garde’s reconsideration of sound and its potential (John Cage, Tony Conrad, Michel Chion et al) alongside the changes of technology over the last century across both analogue and digital media.

In contemporary art we can look to a ‘relational listening’ premise posited by Lawrence English occurring in the relatively recent sonic arts canon. Relational listening is mediated away from traditional ethnography through the ear of both the artist and the microphone during field recordings and their inherent subjectivities; the technical recording is recognised as both a process of creation and reception. In discussing English’s work, Ilmar Taimre highlights the implicitness of crafting or ‘technē’: “for Aristotle, the perceivable outcome or product of technē reveals the necessary existence of a producer or artist as ultimate cause of what is produced.” English escalates our perceptions of ‘world’ through new realms of environmental symbiosis, phenomenological affect, and the collapse or amalgam of time and space through technology - and is synonymous with the artist’s craft in contemporary field recording today.

My field work in and around Dawson City led me to a ‘missing’ film reel that was left behind after an excavation in 1978 uncovered over 500 films that were buried in Dawson City; it was the last stop for the East to West film roadshows across Canada in the early 20th century - after which films were stored or dumped. The military was involved in moving the highly flammable nitrate film reels to Library and Archives Canada and the U.S. Library of Congress for restoration and storage. In 2016 the film, Dawson City: Frozen Time was released by filmmaker, Bill Morrison and scored by Alex Somers. It used the archival footage of the Dawson Film Find (DFF) to piece together found imagery in documentary form that wove a story of the Klondike region and the associated histories of the found films. In August 2019, Bill Morrison was back in Dawson City looking for additional film reels left behind with ideas that there may be still some left in the locale of the 1978 dig or in the Yukon river where films were also dumped during the Klondike Gold Rush. When I encountered a rare missing reel in 2018 that was left behind, I filmed it on my Bolex while struck with a kind of awe. I held the film, it was heavy and on a decayed metal spool. I placed it down into the crack of light coming in from the door and in -30ºC I wound my Bolex and filmed it in detail, I moved it out to the daylight to film the decayed edges on the frames - a signature of erosion that Bill Morrison played with so intently in Dawson City: Frozen Time. I did not want to displace this reel from its liminal snow shack, and I left it, without a can in the freezing temperatures.

Using the 16mm optical printer that was temporarily in my back shed during Covid-19 (our film collective, Artist Film Workshop had to move out of a building scheduled for demolition in Fitzroy, Melbourne in April 2020), I began to run the 16mm film negative through to re-photograph it onto new 16mm film stock. I would print the moving image film over itself in layers, or implement new recursive iterations and distortions upon each frame at a time, sometimes playing with negative and positive rephotography and the pulses of time signatures per frame sequence. This made the film, Resonant Incantations of which I collaborated with Amias Hanley for sounds that they had gathered during field work, too, with the Bogong Centre for Sound Culture.

It may be that in the original act of filming and the act of frame-for-frame rephotography on 16mm film, that I mimicked a similar process to relational listening. My source material of the ‘world’ was filtered through my 1960s Bolex camera, framed by my eye, and decisions again made with technology in the reprinting and distorting of media - albeit with different technology to that of Lawrence English and Amias Hanley. In this sense, I was creating an expanded film reel, spectral and echoing. The difference of ‘relational listening’ is of course the medium of sound. The spatial, vibrational, and penetrative quality of sound is different to that of light. However, the concept of expanded cinema is not to look only to the film but to the periphery.

VIEW RESONANT INCANTATIONS

Catalogue for art purchases coming soon.

Available now:

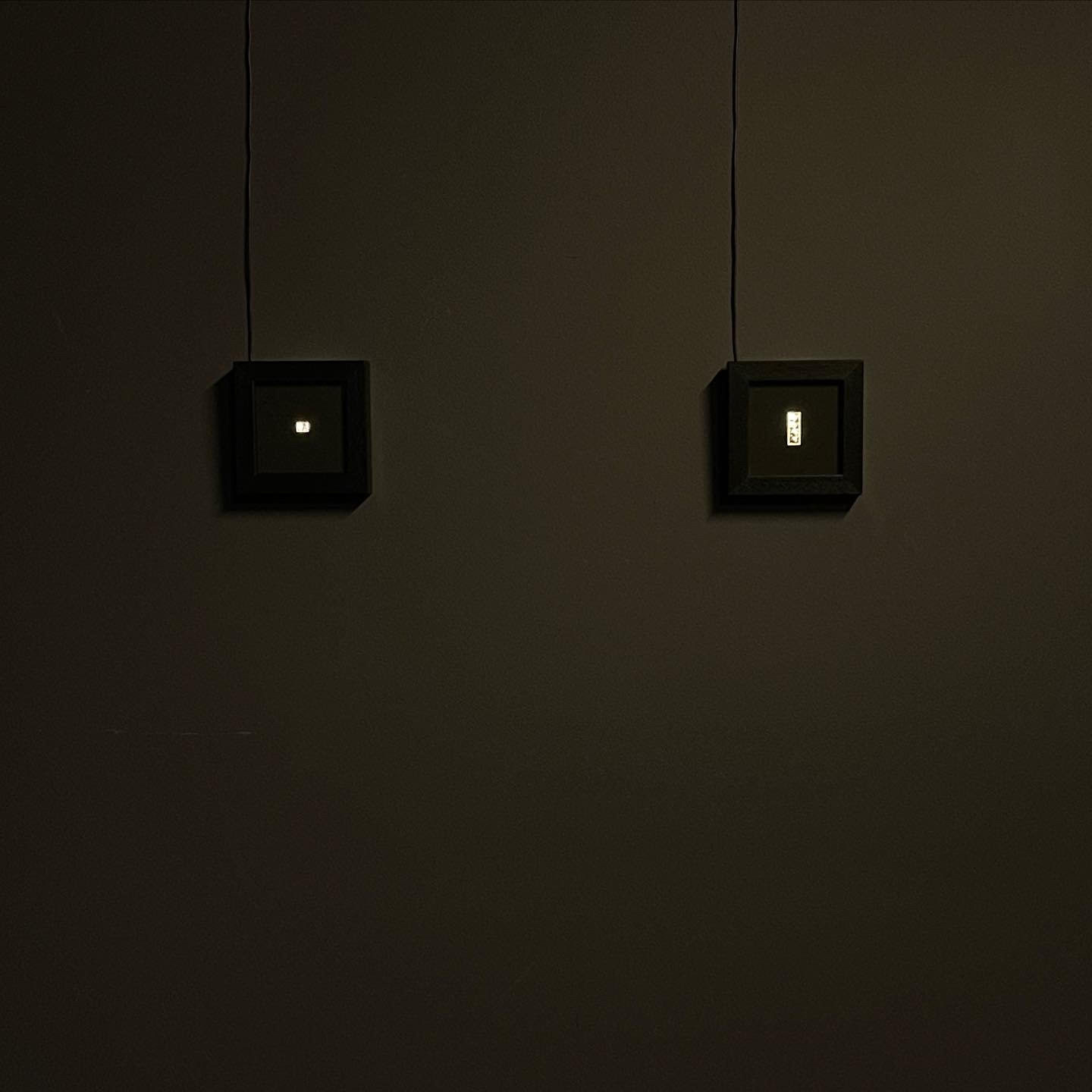

Nightlights $350

Framed 16mm celluloid images, frame size: 13cm x 13cm

and

Archival Pigment Prints

Film stills: 8 x 10” - $120

VIEW FILMS

Enquire directly:

laglina.is [at] gmail dot com

The Last Century Was About History, The Next Will Be About Belief

Exhibition essay by Edward Colless:

The Ship, 16mm kinetic sculpture/film installation

TIME THEORY

In line with a contemporary use of 16mm film, my attempt to finish building a boat out of analogue materials instead of wood and to call it the same boat must assume a perdurantist perspective to make any sense. Persistence of an object is a metaphysical concept of time theory including, but not limited to, Endurance or Perdurance (and later Exdurance not elaborated on here). In theoretical analyses of time, Endurantism (quite simply) refers to objects that “persist by being wholly present at different times.” What causes issues for objects that endure is a concept of change, philosophers of time theory must navigate intrinsic properties that are in flux within an object (consider pregnancy or Theseus’ Ship). Perdurantism thus posits that persistence takes shape through temporal parts - ‘things’ or objects occupy time the same way you occupy space; time is dimensional. The first, middle, and last frame of a film still materially constitutes the same film despite that the frames are not identical - the same as a pregnant woman before, during, and after. A perduring object remains whole across the fourth dimension of time (a spacetime worm) by way of its temporal parts which can contain differing properties. Deleuze considers intrinsic properties of cinema as movement-images in that “each movement-image expresses the whole that changes.” Perdurantism may consider the physical identity of an object as a cumulation of such Deleuzian temporal parts. Noam Chomsky, on the other hand, considers Theseus’ Ship as a psychical conundrum rather than a metaphysical one when drawing out Hume’s position that objects are constructions of thought; Locke’s consideration of personhood to rest upon psychic continuity; and Hobbes argument that properties are characterized by their origins; and right back to Aristotle whereby matter is transformed by use or form – subsequently Chomsky accepts the rhetorical nature (imagine arms thrown in the air here) when he states “it just turns out that our concepts just don’t give an answer.” At which I take liberty whereby The Ship as a whole is not only its original wooden materiality but, as an artwork, embraces both a metaphysical persistence of the ‘object’ through alternate matter and form as well as a possibility through cognition of a speculative ‘reality’ and fiction so that a boat may begin as wood and end up as expanded cinema while retaining an identity of the whole as it persists over time.

In a Sisyphean attempt to finish building my late grandfather’s boat, I believe the object persists as the same boat still, while building it from cinema instead of wood. However, through the process of time and change, it may assume a different character, form, and atmosphere. Much the same can be said of a colony over time - though change, & in which way, can be seen in the hands of those who build it, or tear it down, and/or reconfigure new forms of existence and the metaphysical apparitions of such.

REGARDING FICTION

In world-building for cinema, fictions are put together from foley, scores, images, stories, Shakespearean arcs, montage, or dreamscapes in order to “know” a world. However, as is problematic in documentary practices, conveying a subjective lens upon a ‘real’ location contains a level of bias. In countering this, The Ship reveals its ‘fiction’ by showing us an installation of apparatuses including analogue projectors, 16mm still frames, speakers, and exposed film reels as a disjointed or exposed evocation of a speculative and overtly biased world. A fictional non-linear narrative can be deduced from the arrangement of The Ship’s temporal parts within an installation that cumulatively posits the boat’s identity in flux; the artwork leads us from blueprint, to boat frame, to cinema by presenting fragmented moments conducive to a transhistorical and intermediary world. I consider Frank’s boat as a conduit or a portal that folds together the foreboding natural and site-specific environs of the tropical location (crocodiles, death, the sea) with a subjective ‘tropical gothic’ fiction that de/re-territorialises the boat to live amidst a subversion of the Westernised tropical facade of paradise as seen in bright beaches, neon, and tourism to instead become submerged in a darker undertow that acknowledges the violent construction of Australia by colonisation and patriarchal oppression. As a fictional account of the boat in the event of its material absence, the artwork utilises incongruent visual and aural fragments to conjure it’s presence. Michel Chion established the idea of acousmêtre, whereby a sound or voice can be heard in a film but the source is undetermined. An acousmatic approach for The Ship positions field recordings or foley sounds as temporal parts that are dislocated within time and space yet allusively congruent to the imagery presented and exposes the lie of cinema or the construction of ‘image’ parallel to the lie of colonisation’s paradise.

VISIT THE SHIP

In a Sisyphean attempt to finish building my late grandfather’s boat, I believe the object persists as the same boat still, while building it from cinema instead of wood. However, through the process of time and change, it may assume a different character, form, and atmosphere. Much the same can be said of a colony over time - though change, & in which way, can be seen in the hands of those who build it, or tear it down, and/or reconfigure new forms of existence and the metaphysical apparitions of such.

REGARDING FICTION

In world-building for cinema, fictions are put together from foley, scores, images, stories, Shakespearean arcs, montage, or dreamscapes in order to “know” a world. However, as is problematic in documentary practices, conveying a subjective lens upon a ‘real’ location contains a level of bias. In countering this, The Ship reveals its ‘fiction’ by showing us an installation of apparatuses including analogue projectors, 16mm still frames, speakers, and exposed film reels as a disjointed or exposed evocation of a speculative and overtly biased world. A fictional non-linear narrative can be deduced from the arrangement of The Ship’s temporal parts within an installation that cumulatively posits the boat’s identity in flux; the artwork leads us from blueprint, to boat frame, to cinema by presenting fragmented moments conducive to a transhistorical and intermediary world. I consider Frank’s boat as a conduit or a portal that folds together the foreboding natural and site-specific environs of the tropical location (crocodiles, death, the sea) with a subjective ‘tropical gothic’ fiction that de/re-territorialises the boat to live amidst a subversion of the Westernised tropical facade of paradise as seen in bright beaches, neon, and tourism to instead become submerged in a darker undertow that acknowledges the violent construction of Australia by colonisation and patriarchal oppression. As a fictional account of the boat in the event of its material absence, the artwork utilises incongruent visual and aural fragments to conjure it’s presence. Michel Chion established the idea of acousmêtre, whereby a sound or voice can be heard in a film but the source is undetermined. An acousmatic approach for The Ship positions field recordings or foley sounds as temporal parts that are dislocated within time and space yet allusively congruent to the imagery presented and exposes the lie of cinema or the construction of ‘image’ parallel to the lie of colonisation’s paradise.

VISIT THE SHIP

WHAT IS EXPANDED CINEMA?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Above works and writing by Melody Woodnutt.

Above works and writing by Melody Woodnutt.

Gene Youngblood is credited for coining the term ‘Expanded Cinema’ in his book of the same name in 1970 however in the 1960s, Stan VanDerBeek (an experimental filmmaker known most for his film or media collage works and the dome roofed experiential ‘venue’ Movie Drome) pushed it into use. It was through VanDerBeek’s prolific use of ‘expanded cinema’ in grant applications, publications, the 4th New York Film Festival (1966), and public panels that he began to fortify the term as a loose identity of multi-disciplinary or filmic medias that was as much contrary as synonymous between other expanded cinema artists at the time (Sutton, 2015). Other terms were bounced around as “artists interchangeably used many of the new descriptors coined during this period: New Cinema (Gregory Battcock), Theater of Mixed Means (Richard Kostelanetz), Environmental Theater (Michael Kirby), Intermedia (Dick Higgins), Combine Generation Art (Ken Dewey), Space Theatre (Milton Cohen and ONCE Group),10 Filmstage (Robert Blossom), and Cinema Combine (Sheldon Renan).” Additional descriptors by critics for VALIE EXPORT’s ‘liberated film’ or ‘expanded cinema’ reflects a reconfiguration of cinema as performance including Touch and Tap Cinema (1968) (Fig. 1) or Ping Pong (1968) which was “a feature-length “Spielfilm” or film to be played, points appear on the screen in an alternating rhythm; the actor who stands before the screen must hit these points with a ping-pong paddle and ball”.

At the time of expanded cinema’s conception analogue film and technology was used by experimental film or projection artists that artistically challenged the parameters of both the material and form of moving image. Today in the digital age the difference between expanded cinema and contemporary moving image installation “is largely a question of emphasis…Although a hard core of artists still maintain loyalty to the now-obsolete charms of celluloid film”. In the conceptual realm the use of analogue material can be realised as a choice to engage hauntology, materiality, performativity or liveness and - to a subjective degree - a complicated nostalgia that lives differently today in either the viewer or artist. Emotionally, phenomenologically, or aesthetically - analogue projection glows in literal passing: the residual light of a warm bulb pushing through an image outward lingers in front of the next frame, giving a very different ‘mothlight’ to the high definition of crisp digital projection.

Given the era of expanded cinema’s emergence it “can be read as an expressive manifestation within the overarching trajectory of the framework of the historical European avant garde that includes Futurism, Dada, and the pedagogy advanced by the Bauhaus.” In 1949, Stan VanDerBeek (a leader in the expanded cinema movement) overlapped with R. Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College (BMC) where VanDerBeek “became enamored with Fuller’s message to “immediately apply comprehensive design strategies to enhance communication.”” A genesis of conceptual influence in the coming together of the times lies in the non-hierarchical and artist led Black Mountain College (where teachers and artists alike contributed to the running of the school, including admin, food, and gardens) encourages an ethos of collaboration. Buckminster Fuller and the geodesic dome gave VanDerBeek a structure, MOMA conducted a studio visit to VanDerBeek's Movie Drome which brought Andy Warhol and the New York art elite out for expanded cinema in 1966 to VanDerBeek's Stony Point (NY, USA) locale called “The Land” - a BMC satellite artist colony outside New York which included the likes of John Cage. Through the example of VanDerBeek, expanded cinema was more than an add-on to the cinema frame.

Gene Youngblood, a self confessed passenger of spaceship Earth (denoting his ideological affiliation with R. Buckminster-Fuller) and then faculty member of the California Institute of the Arts, wrote:

“When we say expanded cinema we actually mean expanded consciousness. Expanded cinema does not mean computer films, video phosphors, atomic light, or spherical projections. Expanded cinema isn’t a movie at all: like life it’s a process of becoming, man’s [sic] ongoing historical drive to manifest his consciousness outside of his mind, in front of his eyes. One no longer can specialize in a single discipline and hope truthfully to express a clear picture of its relationships in the environment.”

Expandedness then becomes ecological through multiplicities of consciousness, collaboration, networks of relations, and mediums in a more ontological process of becoming with the world. Employing film, sound and multimedia in an expanded way then relies on the congruence of the consciousness or sub-consciousness of the ‘auteur’ or artist/s and the filmic ability to expand the encountered imagery beyond the frame and into other states (physical, emotional, psychological, phenomenological) that consider our ability to be human in relation to our environment or world (both concréte or an act of othering). That is to say that ecology is inherently concerned with the relation or symbiosis between organisms and their environment: “Thus the act of creation for the new artist is not so much the invention of new objects as the revelation of previously unrecognisable relationships between existing phenomena, both physical and metaphysical. So we find that ecology is art in the most fundamental and pragmatic sense, expanding our apprehension of reality”.

Contemporary art is ripe with cross-disciplinary practices but, for the moving image, what differs between a digital moving image installation and expanded cinema is its artistic heritage - rooted (or rhizome’d) largely in the context of its becoming through experimental analogue techniques alongside ideas of an expanded consciousness, performativity, and non-hierarchical communications. A contemporary relevance in engaging ‘expanded cinema’ is in the peripheries and interstices between medias and their ideologies (sound, phenomenology, analogue film, the frame). We encounter the non-synchronous collapse across time in analogue celluloid film and the hauntology of residual media within an agnostic (dis)belief that film is dead, it is actually its undead corpse that ruptures contemporaneity alongside the collaborative spirit of current and new technologies within artists’ craft.