WHAT IS EXPANDED CINEMA?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Above works and writing by Melody Woodnutt.

Above works and writing by Melody Woodnutt.

Gene Youngblood is credited for coining the term ‘Expanded Cinema’ in his book of the same name in 1970 however in the 1960s, Stan VanDerBeek (an experimental filmmaker known most for his film or media collage works and the dome roofed experiential ‘venue’ Movie Drome) pushed it into use. It was through VanDerBeek’s prolific use of ‘expanded cinema’ in grant applications, publications, the 4th New York Film Festival (1966), and public panels that he began to fortify the term as a loose identity of multi-disciplinary or filmic medias that was as much contrary as synonymous between other expanded cinema artists at the time (Sutton, 2015). Other terms were bounced around as “artists interchangeably used many of the new descriptors coined during this period: New Cinema (Gregory Battcock), Theater of Mixed Means (Richard Kostelanetz), Environmental Theater (Michael Kirby), Intermedia (Dick Higgins), Combine Generation Art (Ken Dewey), Space Theatre (Milton Cohen and ONCE Group),10 Filmstage (Robert Blossom), and Cinema Combine (Sheldon Renan).” Additional descriptors by critics for VALIE EXPORT’s ‘liberated film’ or ‘expanded cinema’ reflects a reconfiguration of cinema as performance including Touch and Tap Cinema (1968) (Fig. 1) or Ping Pong (1968) which was “a feature-length “Spielfilm” or film to be played, points appear on the screen in an alternating rhythm; the actor who stands before the screen must hit these points with a ping-pong paddle and ball”.

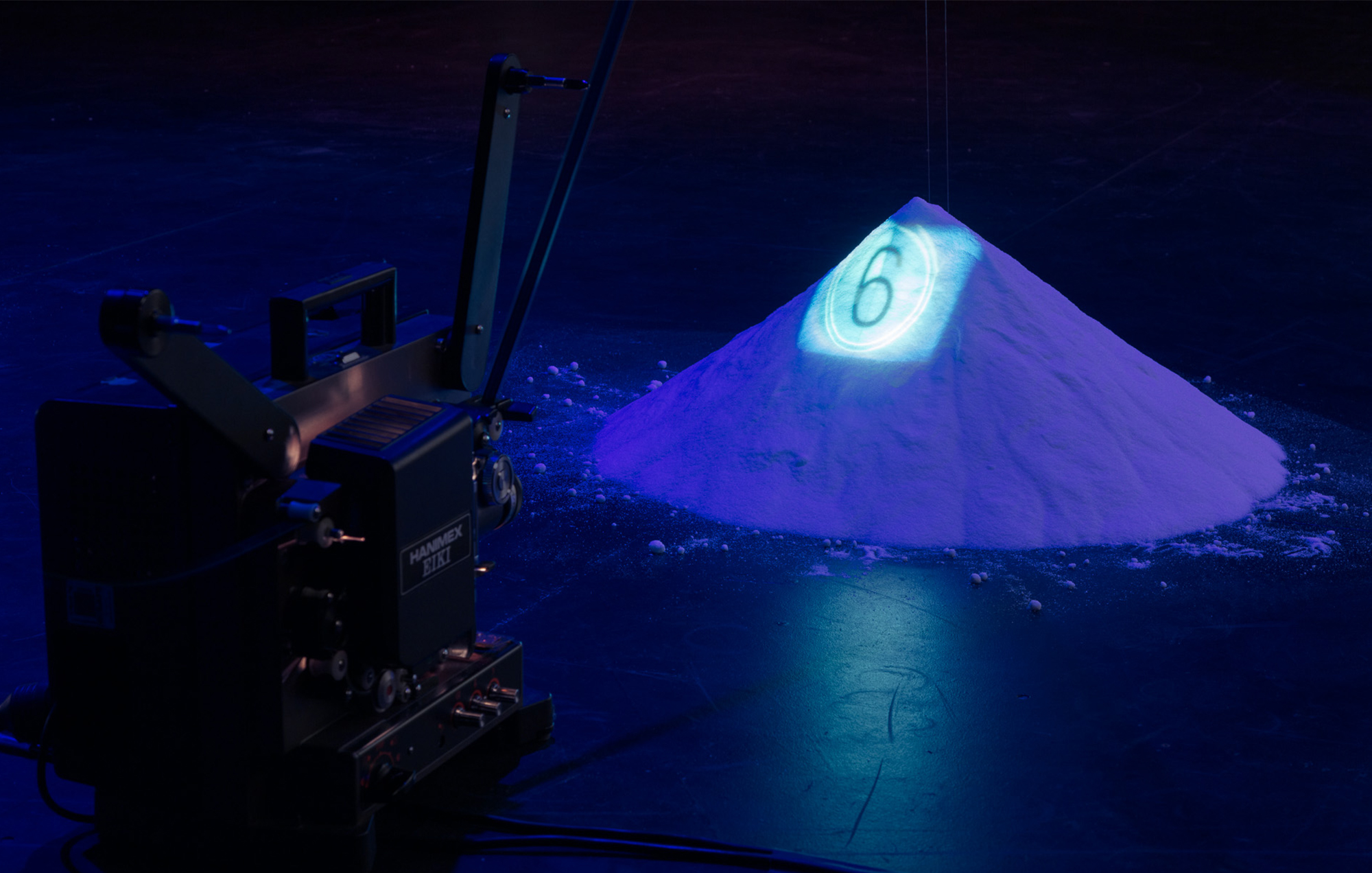

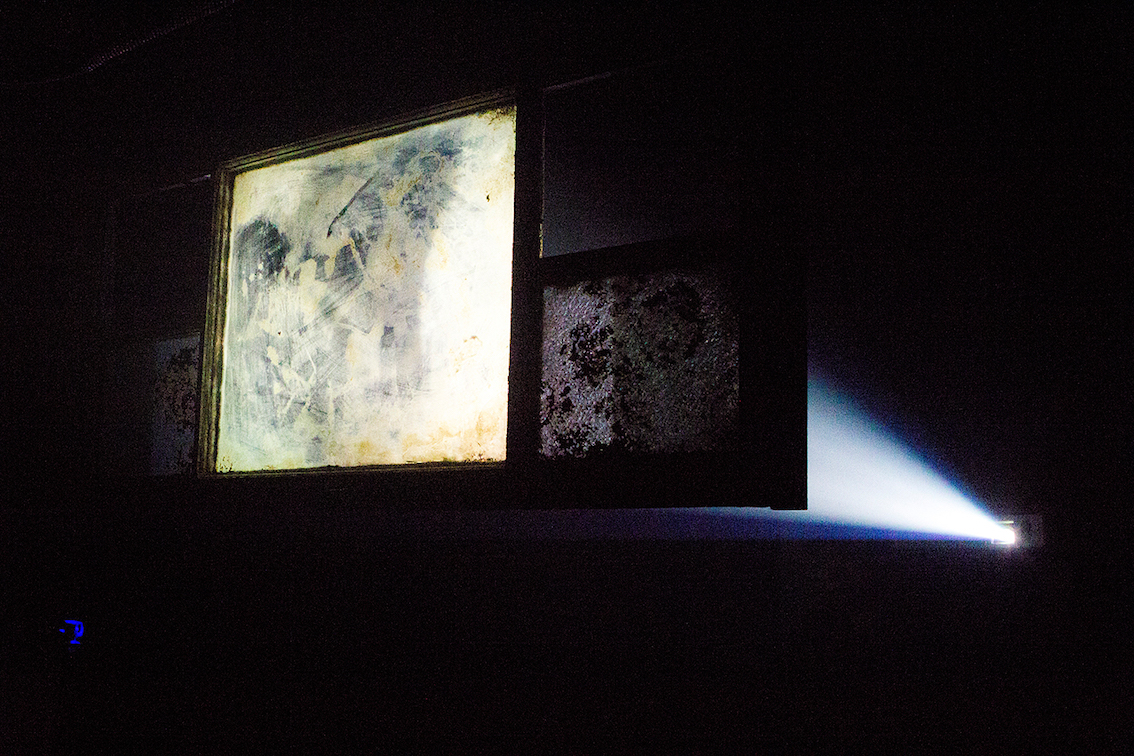

At the time of expanded cinema’s conception analogue film and technology was used by experimental film or projection artists that artistically challenged the parameters of both the material and form of moving image. Today in the digital age the difference between expanded cinema and contemporary moving image installation “is largely a question of emphasis…Although a hard core of artists still maintain loyalty to the now-obsolete charms of celluloid film”. In the conceptual realm the use of analogue material can be realised as a choice to engage hauntology, materiality, performativity or liveness and - to a subjective degree - a complicated nostalgia that lives differently today in either the viewer or artist. Emotionally, phenomenologically, or aesthetically - analogue projection glows in literal passing: the residual light of a warm bulb pushing through an image outward lingers in front of the next frame, giving a very different ‘mothlight’ to the high definition of crisp digital projection.

Given the era of expanded cinema’s emergence it “can be read as an expressive manifestation within the overarching trajectory of the framework of the historical European avant garde that includes Futurism, Dada, and the pedagogy advanced by the Bauhaus.” In 1949, Stan VanDerBeek (a leader in the expanded cinema movement) overlapped with R. Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College (BMC) where VanDerBeek “became enamored with Fuller’s message to “immediately apply comprehensive design strategies to enhance communication.”” A genesis of conceptual influence in the coming together of the times lies in the non-hierarchical and artist led Black Mountain College (where teachers and artists alike contributed to the running of the school, including admin, food, and gardens) encourages an ethos of collaboration. Buckminster Fuller and the geodesic dome gave VanDerBeek a structure, MOMA conducted a studio visit to VanDerBeek's Movie Drome which brought Andy Warhol and the New York art elite out for expanded cinema in 1966 to VanDerBeek's Stony Point (NY, USA) locale called “The Land” - a BMC satellite artist colony outside New York which included the likes of John Cage. Through the example of VanDerBeek, expanded cinema was more than an add-on to the cinema frame.

Gene Youngblood, a self confessed passenger of spaceship Earth (denoting his ideological affiliation with R. Buckminster-Fuller) and then faculty member of the California Institute of the Arts, wrote:

“When we say expanded cinema we actually mean expanded consciousness. Expanded cinema does not mean computer films, video phosphors, atomic light, or spherical projections. Expanded cinema isn’t a movie at all: like life it’s a process of becoming, man’s [sic] ongoing historical drive to manifest his consciousness outside of his mind, in front of his eyes. One no longer can specialize in a single discipline and hope truthfully to express a clear picture of its relationships in the environment.”

Expandedness then becomes ecological through multiplicities of consciousness, collaboration, networks of relations, and mediums in a more ontological process of becoming with the world. Employing film, sound and multimedia in an expanded way then relies on the congruence of the consciousness or sub-consciousness of the ‘auteur’ or artist/s and the filmic ability to expand the encountered imagery beyond the frame and into other states (physical, emotional, psychological, phenomenological) that consider our ability to be human in relation to our environment or world (both concréte or an act of othering). That is to say that ecology is inherently concerned with the relation or symbiosis between organisms and their environment: “Thus the act of creation for the new artist is not so much the invention of new objects as the revelation of previously unrecognisable relationships between existing phenomena, both physical and metaphysical. So we find that ecology is art in the most fundamental and pragmatic sense, expanding our apprehension of reality”.

Contemporary art is ripe with cross-disciplinary practices but, for the moving image, what differs between a digital moving image installation and expanded cinema is its artistic heritage - rooted (or rhizome’d) largely in the context of its becoming through experimental analogue techniques alongside ideas of an expanded consciousness, performativity, and non-hierarchical communications. A contemporary relevance in engaging ‘expanded cinema’ is in the peripheries and interstices between medias and their ideologies (sound, phenomenology, analogue film, the frame). We encounter the non-synchronous collapse across time in analogue celluloid film and the hauntology of residual media within an agnostic (dis)belief that film is dead, it is actually its undead corpse that ruptures contemporaneity alongside the collaborative spirit of current and new technologies within artists’ craft.